4 ways the circular economy can help us manage water

From car manufacturers to local coffee shops, businesses the world over are embracing the circular economy model as they strive for greater sustainability. But the ‘throwaway’ mentality doesn’t only apply to objects which might end up as landfill. These 4 examples show the circular economy can be a game-changer in water management too.

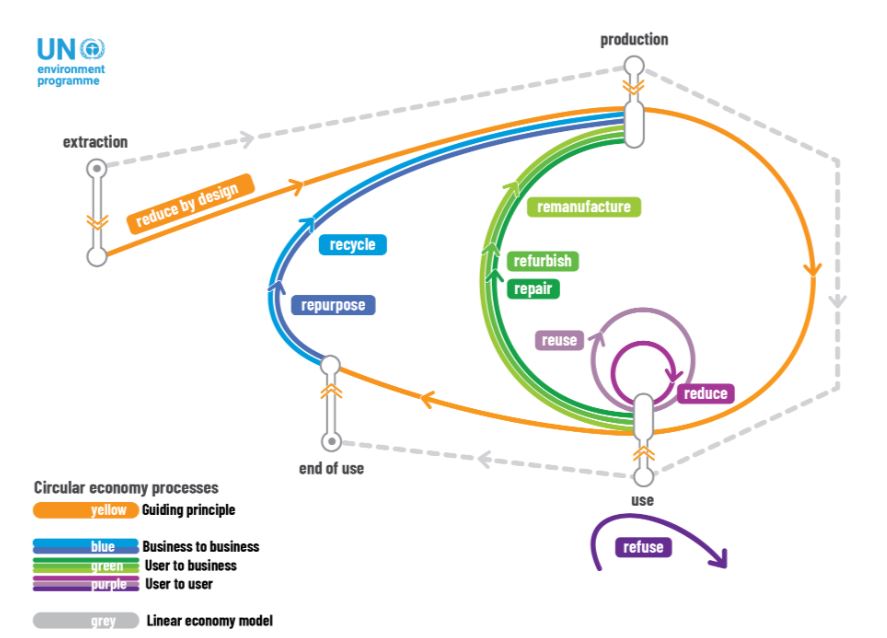

The linear model of production is everywhere in human history, from industry to urban design. We extract natural resources to make products and services – then discard what’s left.

But from plastic waste to carbon emissions, we’re depleting resources and generating waste at astonishing speed. Enter circularity.

The circular economy disrupts the take-make-waste model by shifting our relationship with resources to one of stewardship, where resources are re-used for as long as possible.

As concerns about sustainability grow, the ‘3 Rs’ of circularity – reduce, re-use, recycle – are rewriting the rules of business and consumption. For instance, the drive to “become a circular Google” saw the tech giant claim a zero carbon footprint in 2020.

What does the circular economy mean for water?

Water scarcity is a growing threat. Up to 700 million people could be at risk of displacement because of drought by 2030. The risks to industry are valued at US$301 billion. And over 80% of the world’s wastewater is still released into the environment without treatment. How can the circular economy help?

The circular economy model encourages using less, more wisely. It extends the life cycle of natural resources through three core principles: design out waste and pollution; keep products and materials in use; and regenerate natural resources.

For societies’ biggest consumers of water – including business sectors such as agriculture and textiles, but also city authorities – applying the principles of circularity to water management is not only more sustainable. It makes sound financial sense. Here’s what that looks like in action.

1. Veterans of the circular economy: from waste to facewash

Over 25 years ago, a group of Dutch water utilities joined forces to solve two problems at once: how to reduce costs; and how to dispose of residual minerals which they removed from water in the treatment process.

Adopting an early circular-economy mindset, they took a market-first approach, and collectively looked for ways in which all their by-products could be useful in a different context.

The answer was to repurpose recovered materials such as calcite – otherwise known as lime – and create new products. Now, their waste materials are transformed and sold in 10 different sectors, including pellets for gardening, glass bottles and even a luxurious face scrub.

2. From Concorde to circularity

Filton airfield, near Bristol in the South-West of England, was once the home of Concorde in the UK. Now, as part of the European Union’s ‘Horizon 2020’ funding programme, it will once again be a hub of innovation – this time for circular water solutions.

The airfield will be transformed into a new housing, business and entertainment neighbourhood, where new technology and solutions can be implemented from the inception.

Bringing together 30 organizations in this field, the innovative projects under consideration range from harvesting and storing rainwater from a 10,000m2 roof, to recovering heat from sewage so it can be used to heat a swimming pool or a shopping centre.

3. Replacing water with air in textile dyeing

The textiles sector is extremely water-intensive: according to the United Nations Environment Programme, every year the fashion industry uses 93 billion cubic metres of water – enough to meet the needs of five million people. The UN estimates that one fifth of the world’s wastewater is generated by fabric dyeing and treatment.

A solution by Dutch company DyeCoo is using circular-economy logic to tackle the problem, by reducing water and reusing carbon dioxide (CO2). Its equipment uses captured CO2 to dye textiles in a process which uses no water.

It works because when heated above its critical point, carbon has the properties of both gas and liquid. This results in shorter dyeing times and lower operating costs.

It’s a closed loop process which not only reduces water use, but also links up with broader circular economy aims by using and reusing reclaimed carbon dioxide (which would otherwise contribute to greenhouse gas emissions). The faster, more efficient process also uses 50% less energy.

4. The cities of the future are water-circular

Buiksloterham, a district in the Dutch capital Amsterdam, is a new neighbourhood in every sense of the word. When complete, this former industrial hub will be home to 6,500 residents.

It’s also designed to be circular, as part of the national strategy to adopt a fully circular economy by 2050. Buiksloterham is embracing this through blackwater.

Wastewater from toilets is collected via a vacuum sewer system before treatment with Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket (UASB) reactors.

By-products include biogas (used to produce sustainable energy), nitrogen and phosphorus. Recovering phosphates is a particularly timely intervention: their widespread use in fertilizers has led to depleted reserves and excess amounts in the water cycle, causing damaging levels of pollution. In the circular model, phosphorus is removed and can be reused.

Urban planning partner Metabolic calls Buiksloterham “a living lab for circularity”. They hope that, in the cities of the future, circularity will be second nature.