How architecture plays a role in a water-wise world

Architects are designing water conservation into their buildings – and it could help unlock our future water security.

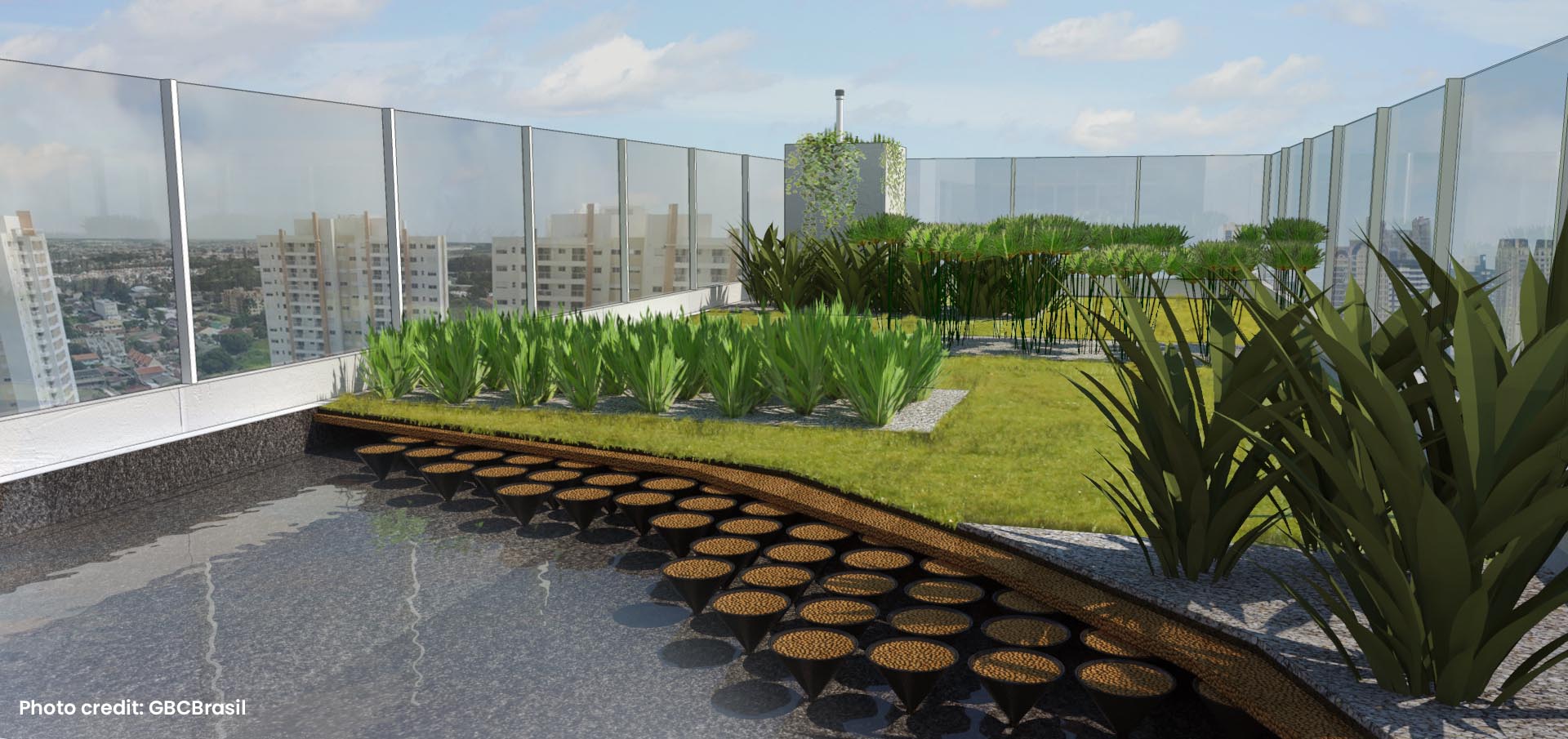

The Eurobusiness office in Curitiba, Brazil is a wide, glass-fronted edifice close to the city’s industrial district. It’s distinctive for its white-striped exterior and wetland roof – and for being the world’s first LEED certified zero water building.

The water-first design ethos of buildings like this one may become commonplace in cities of the future. And as rapid urbanisation and climate change elevate the risks of water scarcity, “blue architecture” could be key to safeguarding this most precious resource.

How do you design water efficiency?

The International Water Association recommends 17 principles for developing water-efficient cities. Some of these dovetail with the ways architects are tackling water conservation, such as reducing consumption and reusing water.

Other principles include embedding visible water, such as water features within structures and blue-green corridors in communities, and designing buildings that play a role in reducing flood risk.

Housebuilders can also empower residents to take ownership of consumption and conservation through:

- Water-efficient plumbing, with smart systems to detect leaks early

- Utilising rain and storm water harvesting, as well as wastewater recycling

- Installing efficient appliances, plus smart meters to display savings in real-time

- Reducing water-intensive garden features (such as turf) and opting for smart sprinklers that irrigate only as needed.

These measures can make a significant difference. According to the American Water Works Association, conventional toilets, showers and faucets consume 60% of the average home’s indoor drainwater. Shifting to low-flow alternatives can reduce consumption by 36%.

Residents save money, too. And because water efficiency is built in, they can do it without the obstacles (and deterrents) of retro-fitting or adopting big lifestyle changes.

3 ways architects are incorporating water into their designs

Communities around the world are finding ways to put water first. Here are three projects that illustrate different ways to build for efficiency and conservation.

1. Brazil’s 14-storey Eurobusiness building goes to great lengths to reduce wastewater. Efficient fixtures help reduce potable water consumption and, as a result, limit waste.

100% of grey and blackwater produced is then treated on-site via a constructed wetland on the roof. This combines a 20cm-deep pool of water to collect rainwater with a raised treatment floor topped with gravel and aquatic plants. Treatment is chemical-free, and the water is then used for flushing toilets and urinals, or infiltrated on site.

Mindful of its space within the community, the building only uses municipally treated drinking water as a backup.

2. Jewel Changi may be a bustling retail complex within Singapore Changi Airport, but it has the calming allure of a rainforest – complete with 2,000 trees and 10,000 shrubs.

Collected storm water cascades through the glass roof, creating the world’s tallest indoor waterfall. Run-off is pumped around the building and back to the oculus, forming a continuous cycle. When the rainwater tanks are full, excess water is used for irrigation.

At night, the rain vortex becomes the backdrop to a sound and light show. However, Peter Kopik, of design firm WET says this isn’t just a novelty feature: the water is a continuation and completion of the building itself.

3. One neighbourhood of Vinge city, Denmark is appropriately named The Delta District – a man-made delta designed to reduce the city’s risk of flooding.

A network of trenches and basins channels rainwater into the delta from around the district but, unlike conventional drainage systems and pipes, these remain visible rather than hidden away. In fact, designers SLA architects intend this to be a focal point of the district once its completed.

During dry periods, the channels and basins will dry out, forming green trenches. During rainy periods, they’ll fill with water. Either way, they become habitats for wildlife and recreation areas for residents alike. Rather than a decorative feature, water here has a purpose within the community.

These examples show how water can sit at the heart of community and corporate design, transforming our relationship with conservation and consumption.

By seeing and interacting with natural resources, the people who fill these spaces can become more aware of the importance of water – and draw their own conclusions about how best to preserve it in their homes and communities.