What guides decisions on an invaluable resource? Insights from the Valuing Water Survey

What values guide those who take decisions about water on a daily basis? Do people’s personal values matter for how they look at water management problems? What are strategic priorities for the global water governance agenda, and how do these represent different values? What is, after all, good water governance?

These are just some of the questions that we sought to answer with the Valuing Water Survey: the first global survey on values targeted at water professionals. Designing and implementing this ambitious survey (which was available in seven world languages) was motivated by a paradigm shift in global water governance, towards making explicit the value footprint that underpins water policy and decisions about water.

When we talk about valuing water, often, what we really mean is: what value does water have to humans. Perhaps unsurprisingly, respondents ascribed a wide variety of values to water, which can be broadly summarised as economic values (e.g. agricultural produce derived from irrigation; renewable energy from hydroelectric power stations), environmental values (e.g. rivers and lakes as habitat for aquatic plants and animals) and as cultural values (e.g. the sense of identity attached to rivers and lakes in particular places; the spiritual importance of water in many cultures around the world).

Although most of us will recognise these three types of values of water, some respondents felt that water governance is sometimes disproportionately geared towards just one of them, and that we need to ensure that collective decisions about water strike a good balance between benefiting the economy but also serving the needs of aquatic biodiversity and maintaining cultural traditions.

Beyond the values of water, we also investigated the values or principles that should be followed to ensure good governance of water resources. Valuing water is also about the weight given to consequences of certain choices and actions that affect water (and thus, the value of water for others). Here, our survey suggested that there are two main perspectives. The first revolved around the values of efficiency, competition, effectiveness, simplicity and adaptability. From this perspective, water governance should run smoothly like an oiled machine, always striving for better performance.

The second perspective revolved around conceptually different values, such as social justice, cooperation, transparency, public participation, accountability, and gender equality. Evidently, this is a very different set of priorities, but also easily recognisable to those active in the water sector. While being inclusive of a wide range of perspectives may sometimes stand in the way of being quick and efficient, it is also important. If one values perspective consistently dominates, the space for other values shrinks.

One respondent commented that valuing water goes beyond just identifying the values of water: “The way we see/value water is also an indicator of how we understand ourselves as persons.” In line with this broader vision, we also investigated how personal values were linked to respondents’ preferences with regards to strategic priorities for the global water governance agenda.

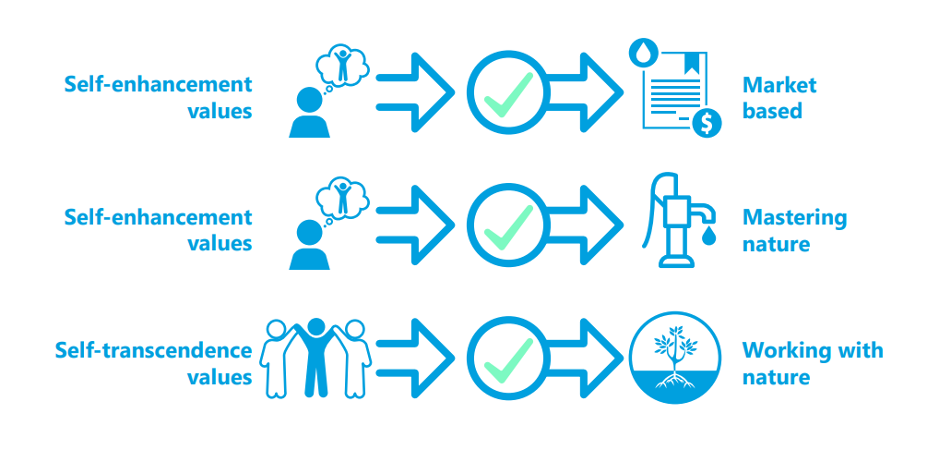

We summarised these strategic priorities as either mastering nature (through engineering or financial incentives), working with nature (through reducing our collective human footprint on water) and market-based water management (through using market mechanisms to improve water governance).

We found that respondents who prioritised personal values such as success, achievement, and power (often summarised as ‘self-enhancement values’) or governance-related values such as efficiency and competition (as outlined above), were more likely to endorse policy instruments such as water markets, charges for domestic access to water, and privatisation of water and sanitation utilities.

They also supported a vision in which humans were active managers of water resources, through civil engineering interventions, expansion of irrigation capacity, investment in water supply infrastructure, dams, and water treatment technology.

Conversely, those who prioritised personal values such as helping others, caring about the poor and marginalised, as well as the natural environment (often summarised as ‘self-transcendence values’) or governance-related values such as social justice and cooperation (as outlined above) were more supportive of policy instruments that seek to reduce humanity’s impacts on water resources. These are, for example, nature-based solutions for flood risk management, reducing domestic water consumption, and investing in energy and water saving technologies

These findings suggest that our personal values resonate even in matters such as water policy, and in the decisions we take or would like to see taken about water.

Moving forward, we need to be aware of the importance of different values perspectives on water. Those different perspectives should resonate in policies and decisions. If a single values perspective dominates, then other values will decline. An economy cannot exist without nature; it is embedded in nature. Culture will degrade if spiritual practices that used to be performed in healthy rivers have to adjust to doing so in open sewers. And if wetlands in one region no longer release water vapour into the atmosphere, then that may affect rainfall in another region where the economy depends on reliable rainfall. Water flows through all veins of society, the economy and nature. It changes identity and morphs from a common good into a private good and back, multiple times on its way from source to sea.

Therefore, we need to respect and value all points of view, learn to listen more to those we disagree with, and ensure that water governance reflects a wide variety of (personal, governance-related and water) values. In particular, we need to ensure that the values of those that may have been marginalised in decision-making are considered, which requires conscious empowerment. We believe that a values lens is a useful addition to the water governance toolkit.

Here we summarise some of the main findings and implications of the Valuing Water Survey; more detailed insights can be found here. We have also chosen to make the survey available for a longer period of time, since a larger sample may allow us to conduct further analyses. We would particularly encourage responses from professionals working in the private sector, as well as from North America, Asia, and the Middle East, which are currently underrepresented in our sample.

Survey is in this link: https://bathpsychology.eu.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_7VAx90JlwMzSR0O

If you are attending Stockholm World Water Week 2022, please join us at our online session on Wednesday, 24 August, 17:00-18:20, where we will be presenting and discussing survey findings and policy implications.

About the authors

Dr Christopher Schulz is lead researcher for the Valuing Water Initiative. His PhD research covered conceptual and empirical dimensions of valuing water, with fieldwork in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso.

He developed the Valuing Water Survey in collaboration with Dr Lukas Wolf (Department of Psychology, University of Bath), Professor Julia Martin-Ortega (Sustainability Research Institute, University of Leeds) and Dr Klaus Glenk (Department of Rural Economy, Environment and Society, Scotland’s Rural College, Edinburgh).

Maarten Gischler is Senior Water Adviser with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands.